Introduction (TS 1.0) #

Definition #

- Consider data of the same nature that have been observed at different points in time

- The mere fact that they are of the same nature means that they are likely related in one way or another - let’s call those `correlations’

(an acceptable term in this context as we focus on this measure, at least in this course) - This is in contrast with the usual “i.i.d.” assumptions associated with a sample of outcomes of a random variable

- This invalidates some of the techniques we know, and brings additional difficulties, but also opportunities! (such as forecasting)

Definition: “The systematic approach by which one goes about answering the mathematical and statistical questions posed by these time correlations is commonly referred to as time series analysis.”

Applications #

The applications of time series are many, and crucial in many cases:

- Economics: unemployment, GDP, CPI, etc

- Finance: share prices, indices, etc

- Medicine: COVID-19 cases and fatalities, biometric data for a patient (blood pressure, iron levels,

- Global warming: ocean temperatures,

- Actuarial studies: frequency and severity of claims in a LoB, mortality (at different ages, in different locations,

Process for time series analysis #

Sketch of process:

- Careful examination of data plotted over time (Module 7)

- Compute major statistical indicators (Modules 7 and 8)

- Guess an appropriate method/model for analysing the data (Modules 8 and 9)

- Fit and assess your model (Module 9)

- Use your model to perform forecasts if relevant (Module 10)

We distinguish two types of approaches:

- Time domain approach: investigate lagged relationships (impact of today on tomorrow)

- Frequency domain approach: investigate cycles (understand regular variations)

In actuarial studies, both are relevant.

Examples (TS 1.1) #

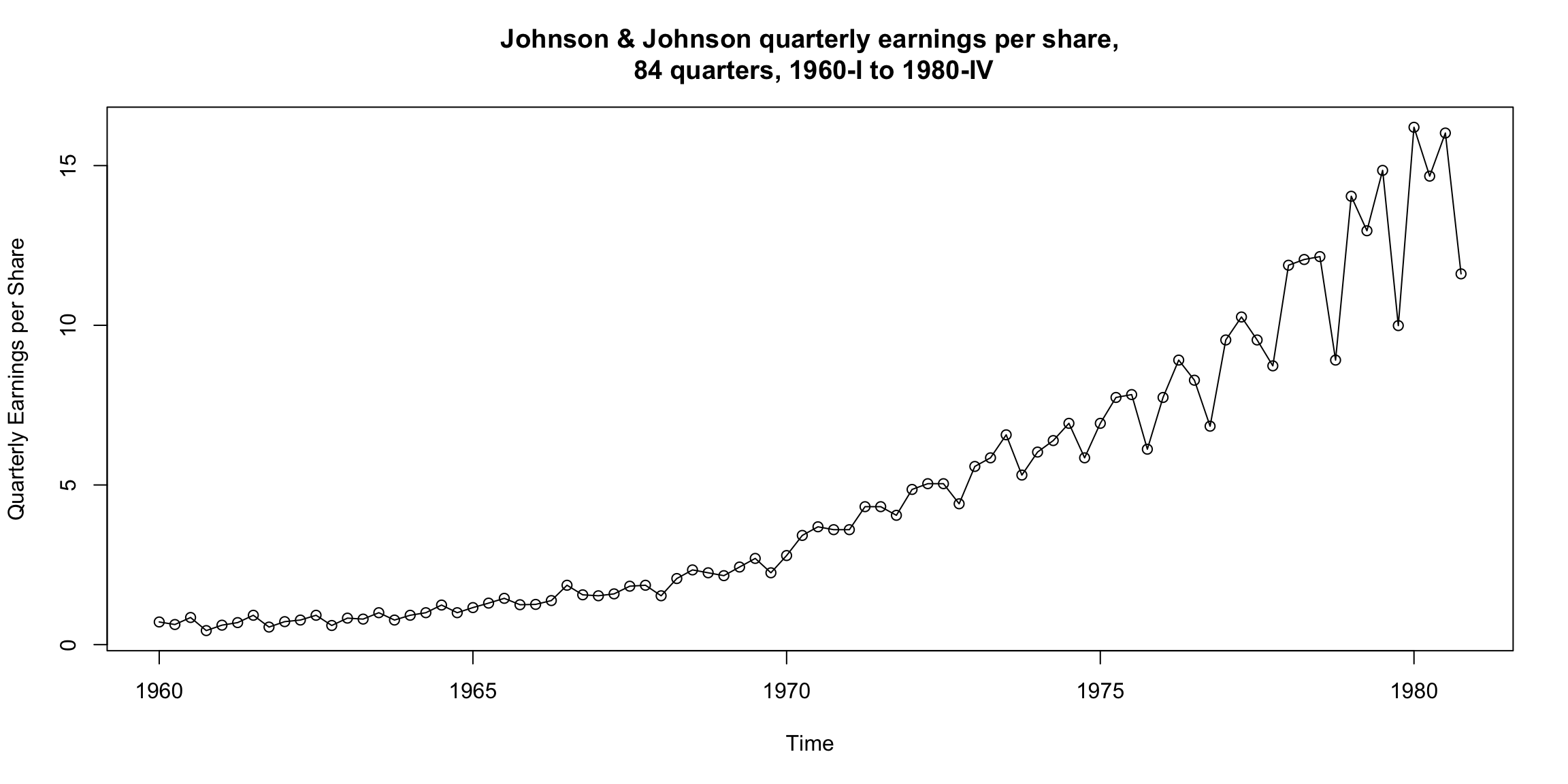

Johnson & Johnson quarterly earnings per share #

What is the primary pattern?

Can you see any cyclical pattern as well?

How does volatility change over time (if at all)?

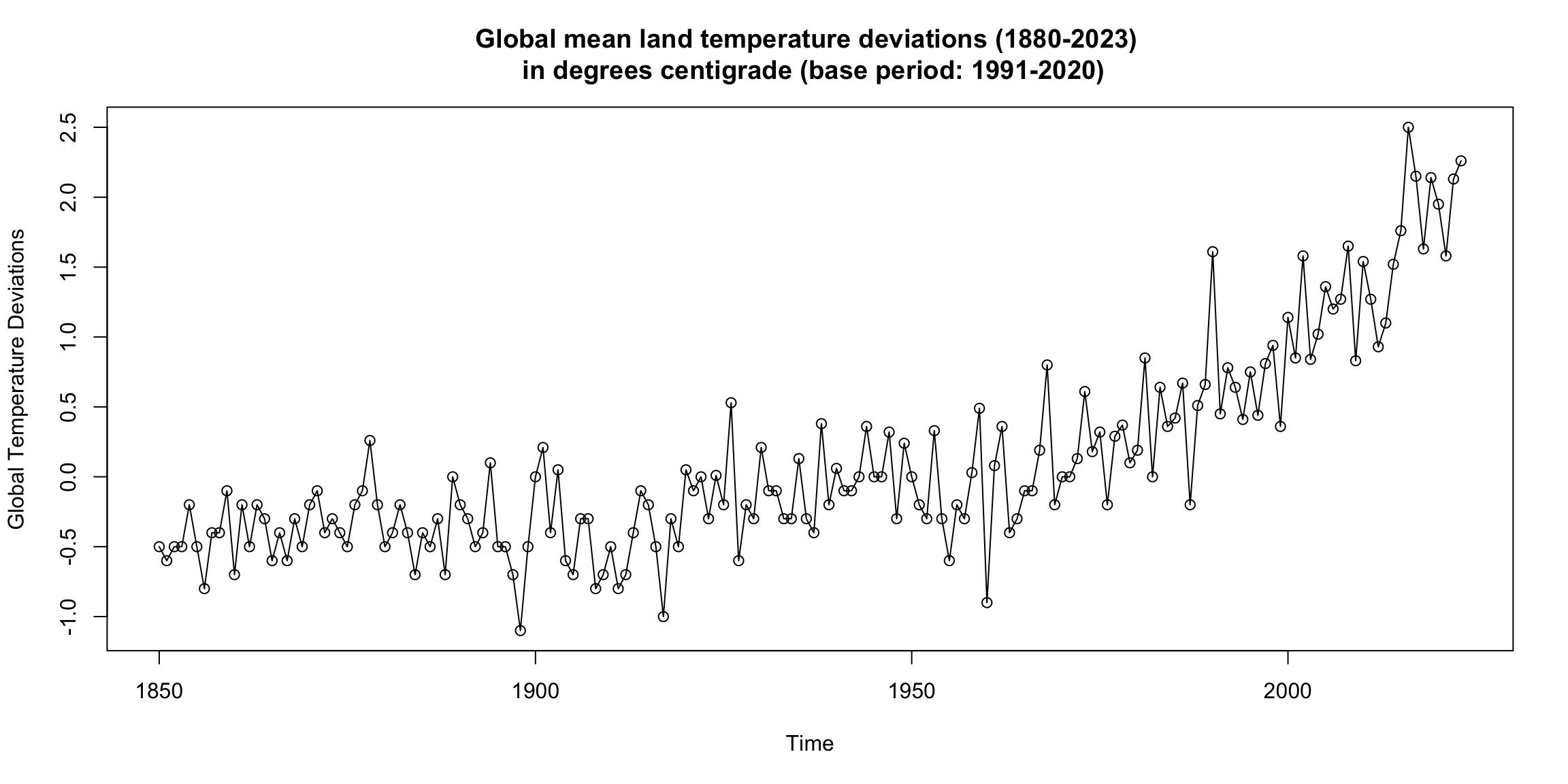

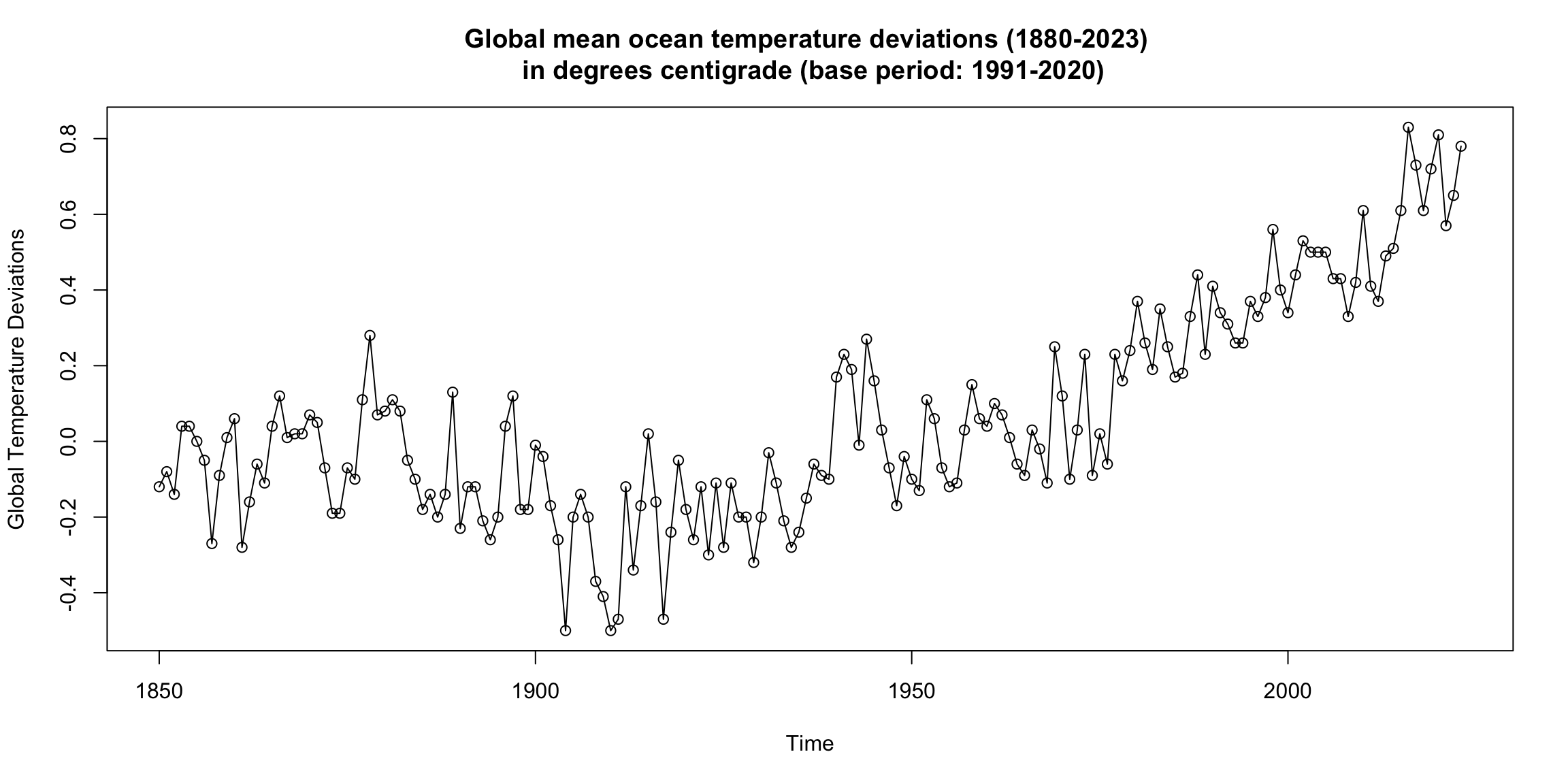

Global mean land-ocean temperature index #

Can you see a trend? Are there periods of continuous increase?

What would be the main focus for global warming: trend or cycles?

How do these graphs support the global warming thesis?

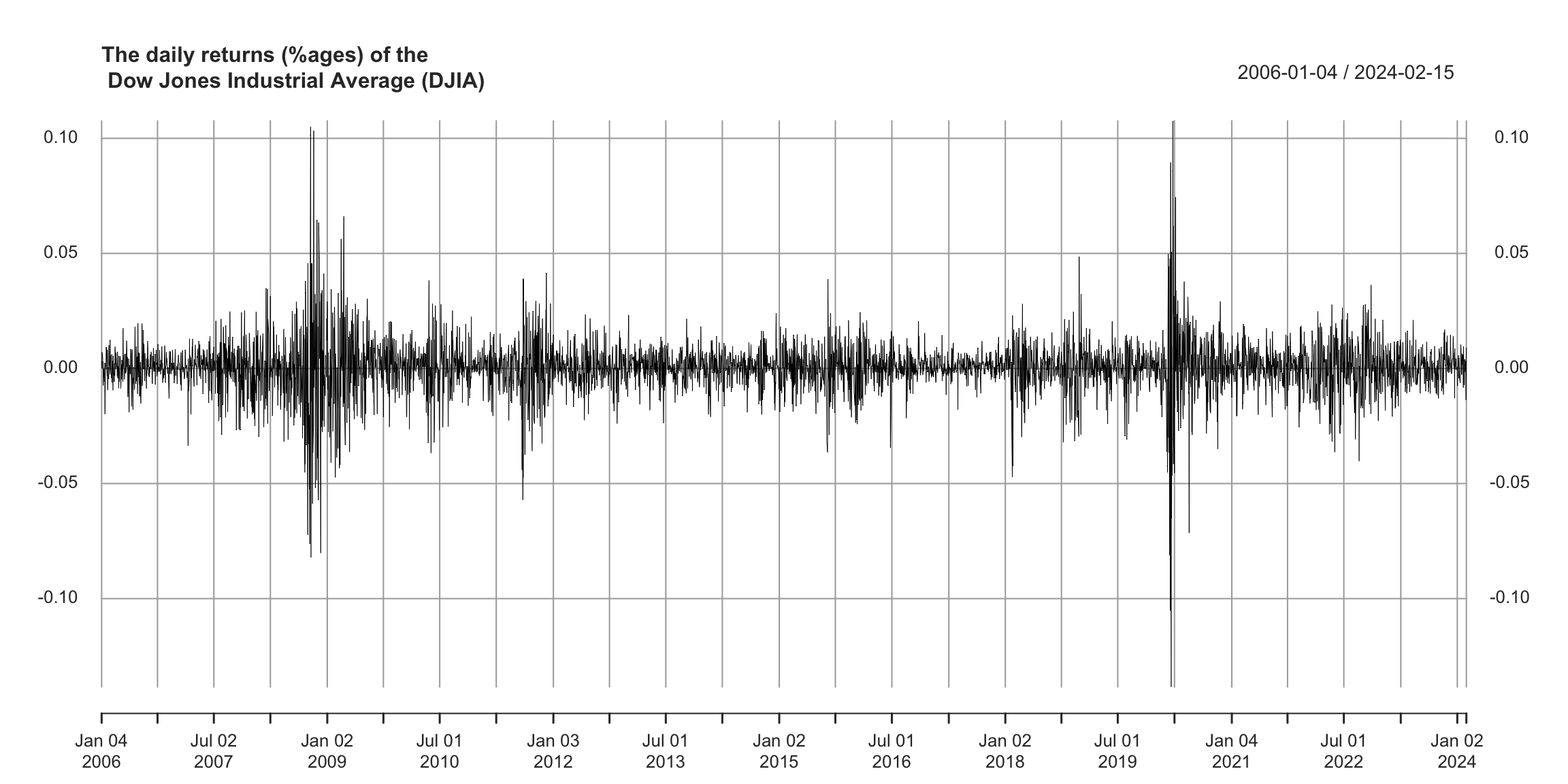

Dow Jones Industrial Average #

How is this time series special?

What qualities would a good forecast model need to have?

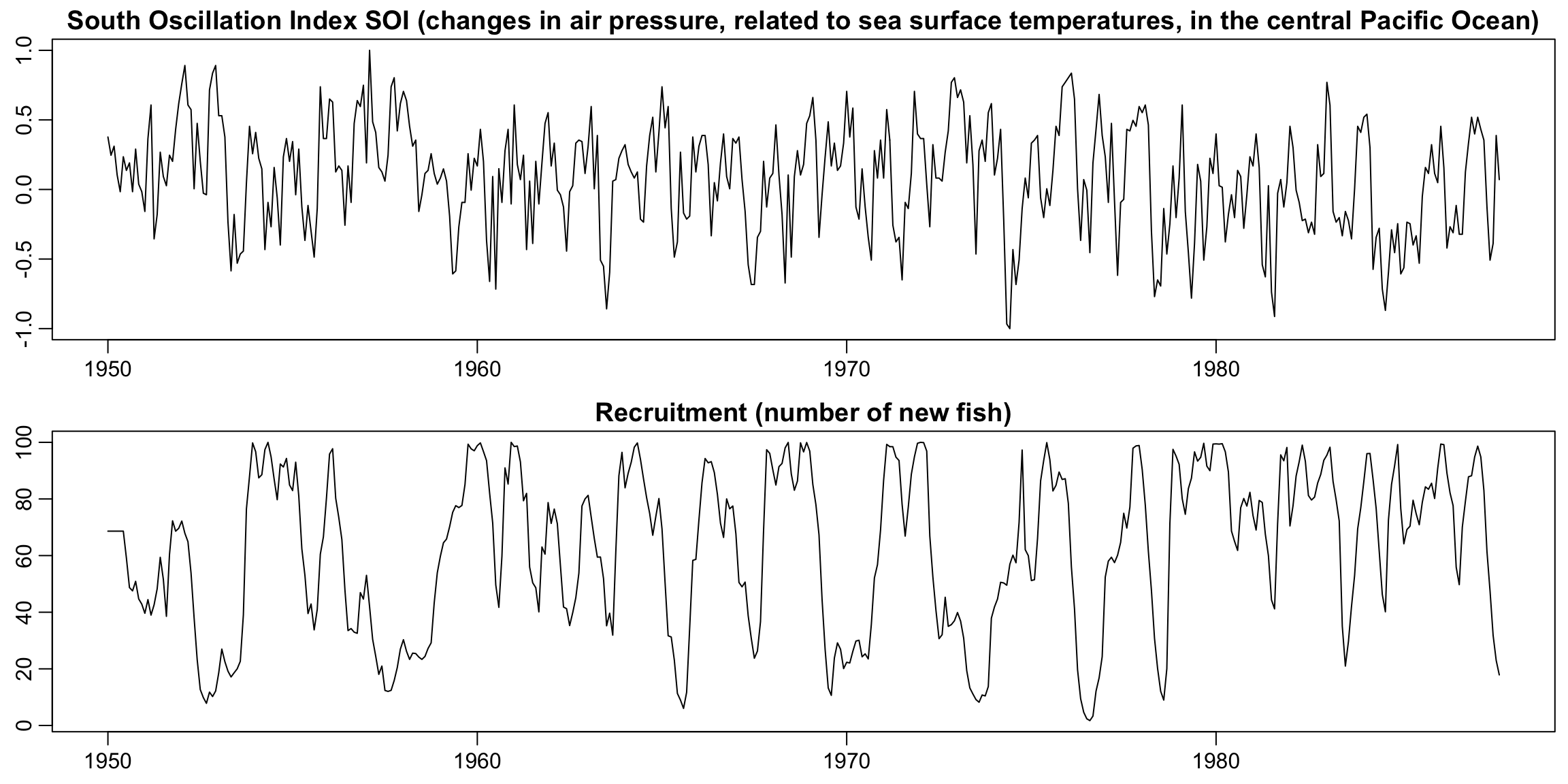

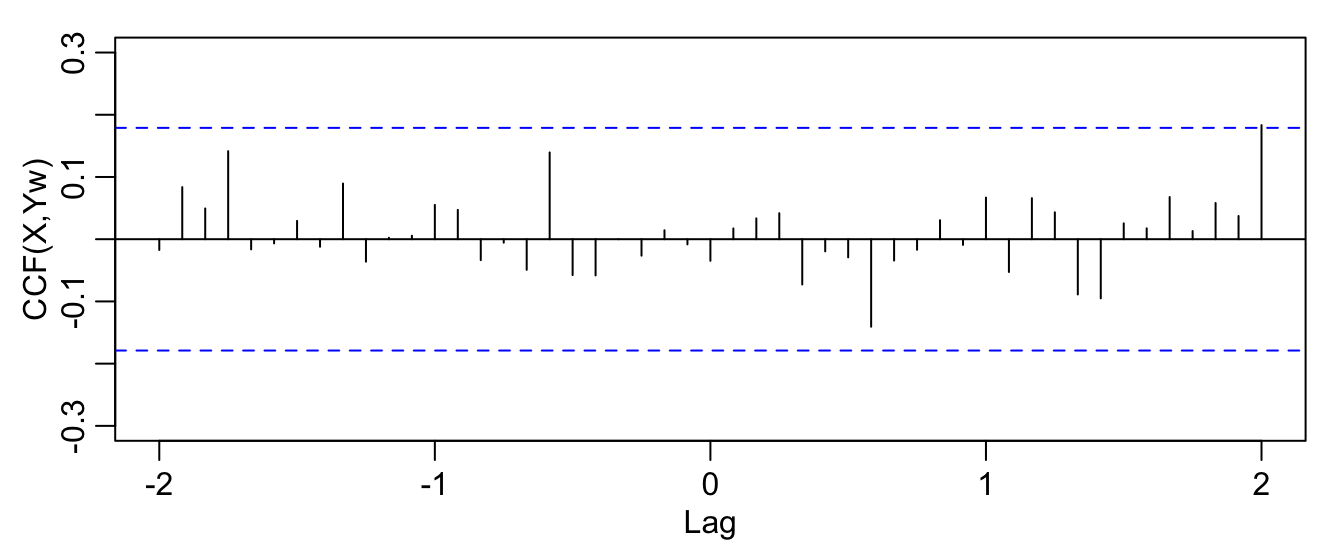

Analysis of two series together: El Niño & fish population #

How many cycles can you spot?

Is there a relationship between both series?

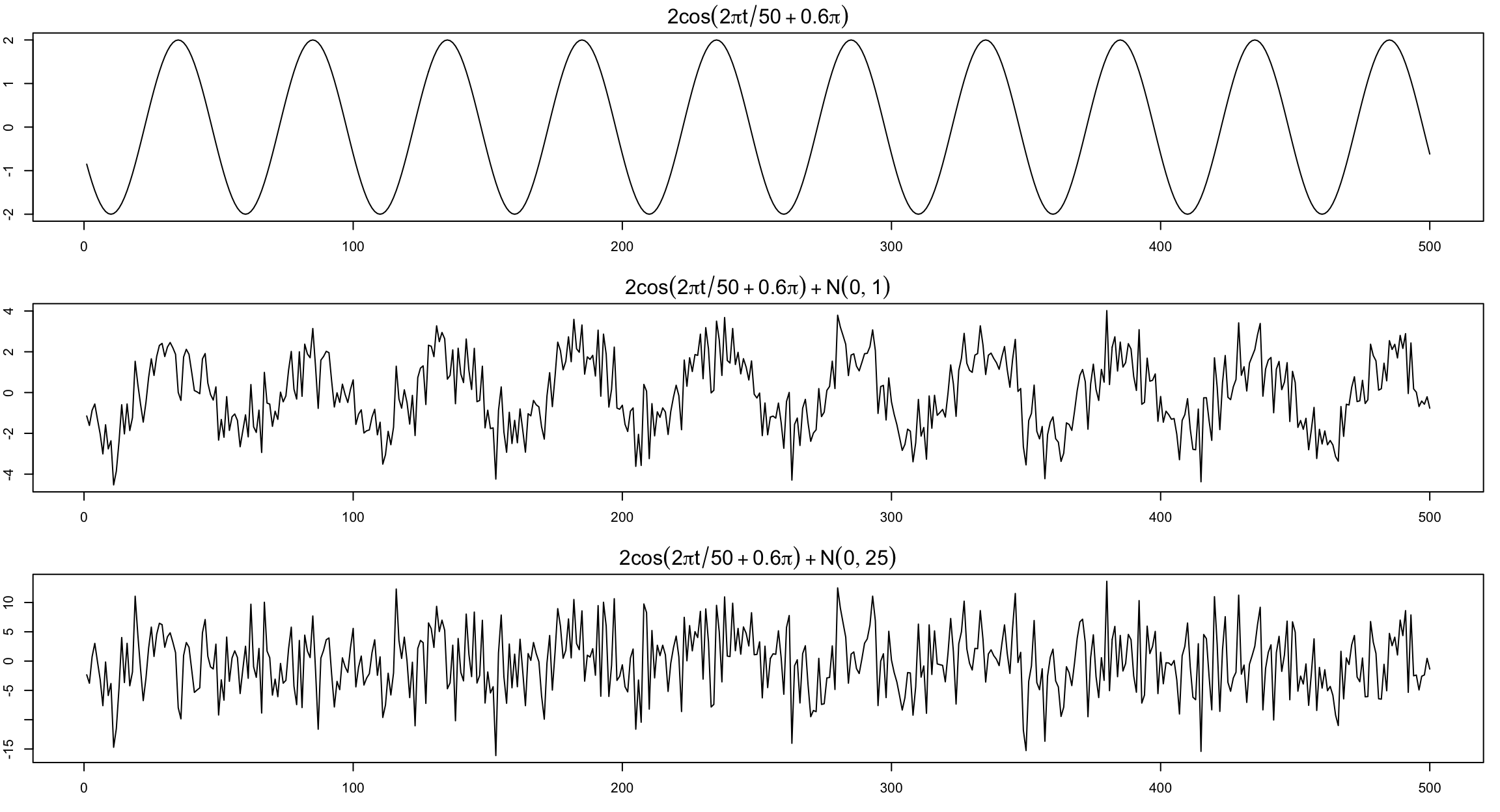

Signals within noise #

Typically we only see the the signal obscured by noise.

Basic models (TS 1.2) #

Preliminaries #

- Our primary objective is to develop mathematical models that provide plausible descriptions for sample data

- A time series is a sequence of rv’s

- In this course,

- One set of observed values of

- Time series are usually plotted with time in the

- Sampling rate must be sufficient, lest appearance of the data is changed completely (aliasing; see also

thiswhich explains how car wheels can appear to go backwards) - Smoothness of the time series suggests some level of correlation between adjacent points, or in other words that

White noise - 3 scales :-) #

Let’s define

- White independent noise: (or iid noise) additional assumption of iid, denoted

- Gaussian white noise: further additional assumption of normal distribution, denoted

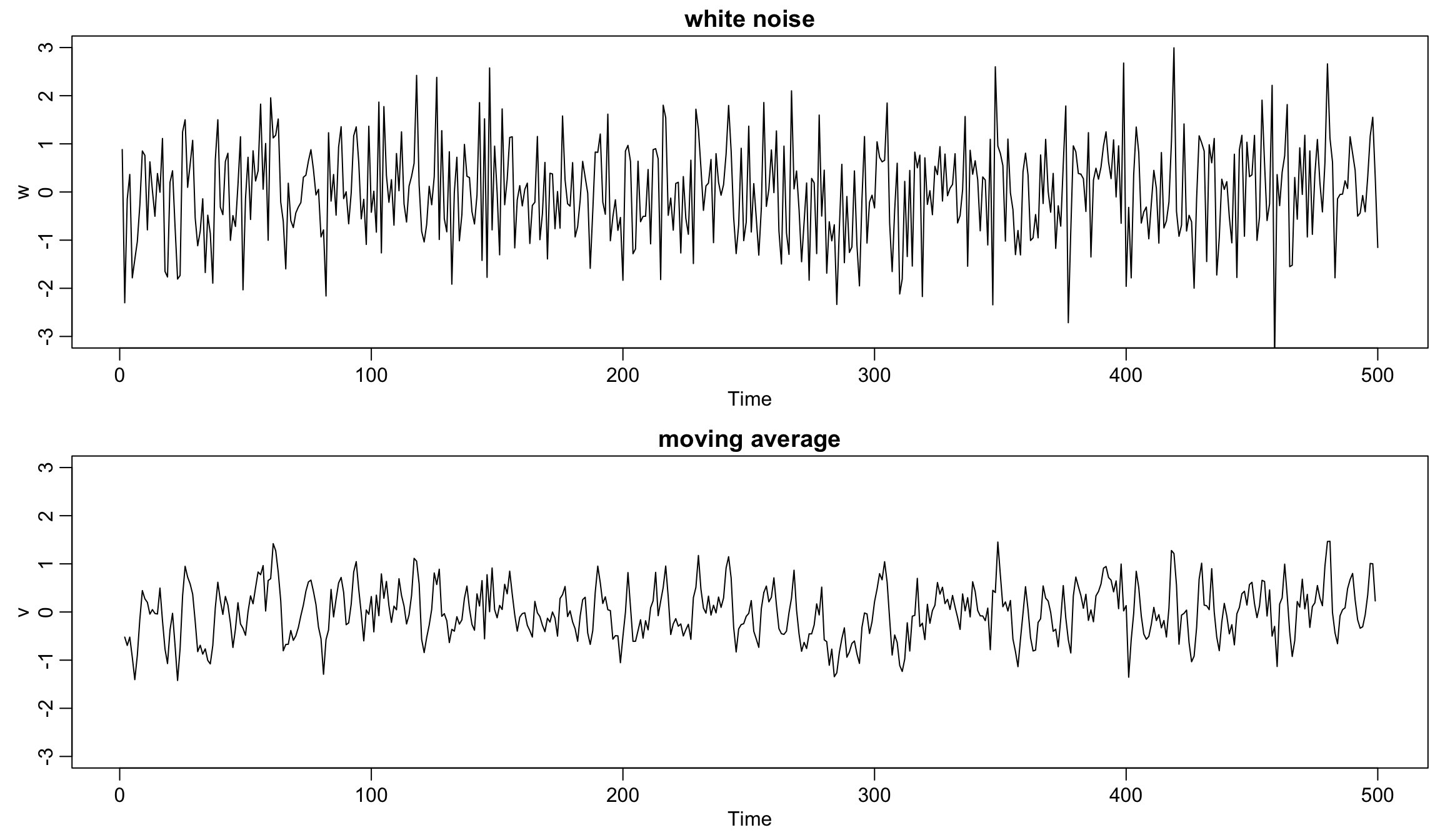

Gaussian white noise series and its 3-point moving average #

w <- rnorm(500, 0, 1) # 500 N(0,1) variates

plot.ts(w, ylim = c(-3, 3), main = "white noise")

v <- stats::filter(w, sides = 2, filter = rep(1/3, 3)) # moving average

plot.ts(v, ylim = c(-3, 3), main = "moving average")

Filtering (and moving average) #

A series

-

Example: 3-point moving average (see bottom of previous slide for graph):

-

In R, moving averages are implemented through the function

filter(x, filter, method = c("convolution"),sides = 2)where

xis the original series,filteris a vector of weights (in reverse time order),method = c("convolution")is the default (alternative isrecursive), and wheresidesis 1 for past values only, and 2 if weights are centered around lag 0 (requires uneven number of weights). -

Moving average smoothers will be further discussed in Module 8.

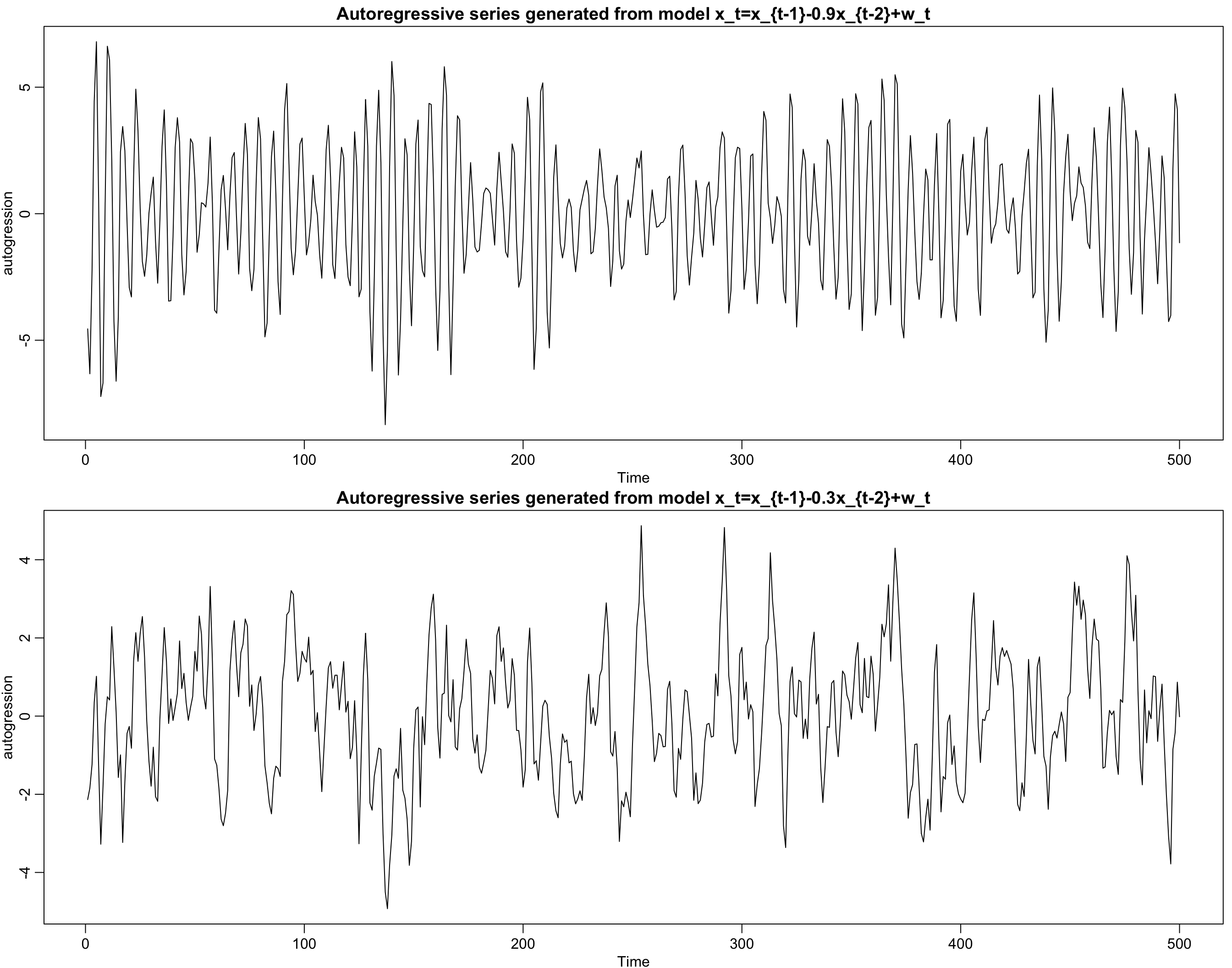

Autoregressions #

A series

-

Example: An autoregression of the white noise:

-

If the autoregression goes back

filterwill use 0’s otherwise). -

In R, autoregressions are implemented through the function

filter(x, filter, method = c("recursive"),init)where

xis the original series,filteris a vector of weights (reverse time order) andinita vector of initial values (reverse time order). -

Autoregressions will be denoted

# take this series:

wt <- 1:10

# a simple filter:

filter(wt, rep(1/3, 3), method = c("convolution"), sides = 1)

## Time Series:

## Start = 1

## End = 10

## Frequency = 1

## [1] NA NA 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

# an autoregression

filter(wt, rep(1/3, 3), method = c("recursive"))

## Time Series:

## Start = 1

## End = 10

## Frequency = 1

## [1] 1.000000 2.333333 4.111111 6.481481 9.308642 12.633745

## [7] 16.474623 20.805670 25.638012 30.972768

# note how the previous _results_ (rather than wt) are

# being used in the recursion

Autoregression examples #

w <- rnorm(550, 0, 1) # 50 extra to avoid startup problems

x <- stats::filter(w, filter = c(1, -0.9), method = "recursive")[-(1:50)]

# remove first 50

plot.ts(x, ylab = "autogression", main = "Autoregressive series generated from model x_t=x_{t-1}-0.9x_{t-2}+w_t")

y <- stats::filter(w, filter = c(1, -0.3), method = "recursive")[-(1:50)]

# remove first 50

plot.ts(y, ylab = "autogression", main = "Autoregressive series generated from model x_t=x_{t-1}-0.3x_{t-2}+w_t")

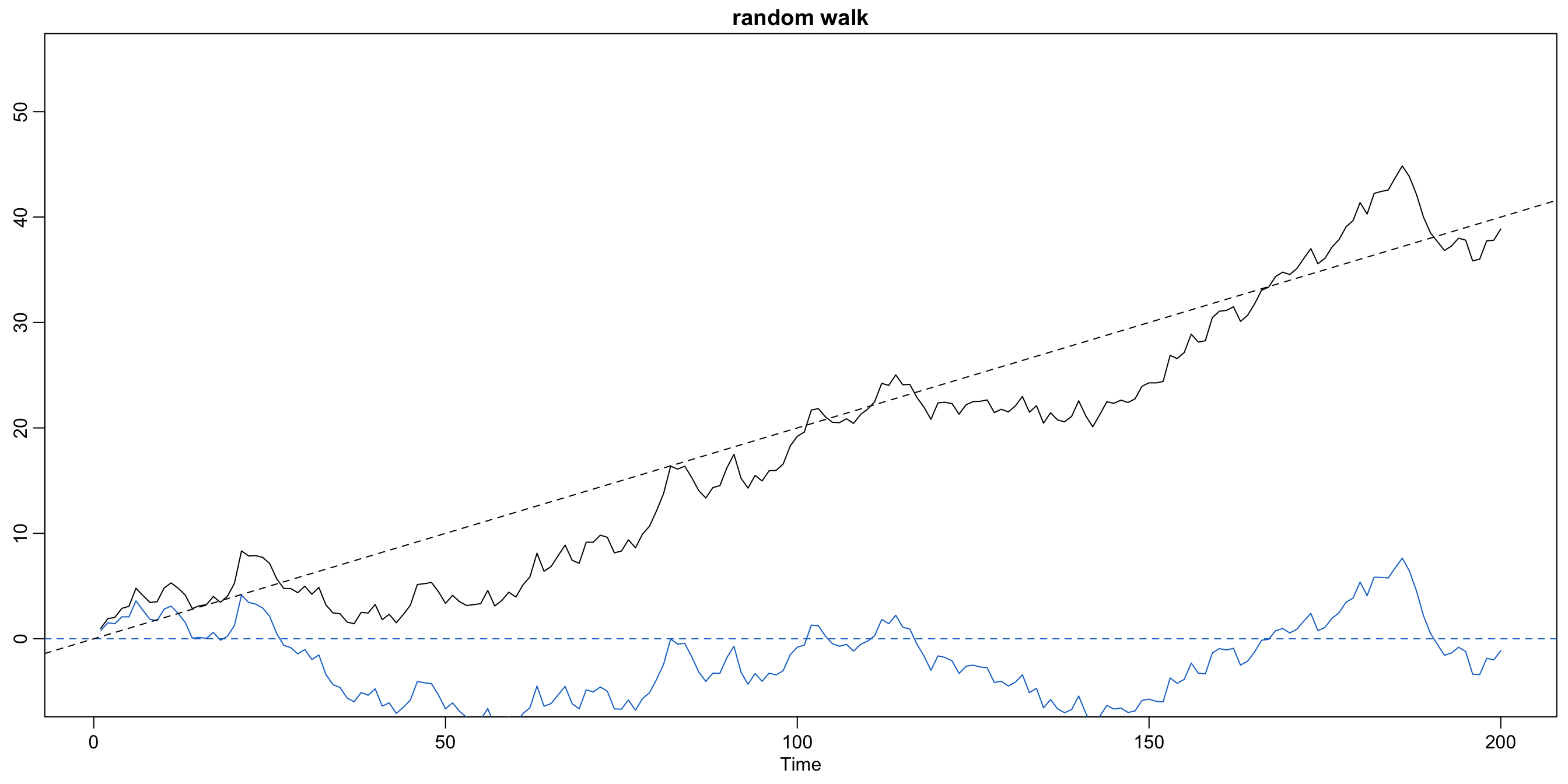

Random walk with drift #

- The autoregressions introduced above are all centered around 0 for all

- Assume now that the series increases linearly by

- The random walk with drift looks back only one time unit:

- If

- The term can be explained by visualising each increment from

Random walk with drift

Code used to generate the plot:

set.seed(155) # so you can reproduce the results

w <- rnorm(200)

x <- cumsum(w)

wd <- w + 0.2

xd <- cumsum(wd)

plot.ts(xd, ylim = c(-5, 55), main = "random walk", ylab = "")

lines(x, col = 4)

abline(h = 0, col = 4, lty = 2)

Describing the behaviour of basic models (TS 1.3) #

Motivation #

-

In this section we would like to develop theoretical measures to help describe how times series behave.

-

We are particularly interested in describing the relationships between observations at different points in time.

Full specification #

- A full specification of a time series of size

- Examination of the margins

- These are very theoretical. In practice, one often have only one realisation for each

What would be the most basic descriptors?

Mean function #

The mean function is defined as

Examples:

- Moving Average Series: we have

- Random walk with drift: we have

Autocovariance function #

The autocovariance function is defined as the second moment product

- We will write

- This is a measure of linear dependence.

- Smooth series

- Choppy series

- [

For two series

Examples of autocovariance functions #

White noise: The white noise series

Remember that if

Moving average: A 3-point moving average

This is related to the concept of weak stationarity which will introduce later.

Random walk: For the random walk

Also

The autocorrelation function (ACF) #

The autocorrelation function (ACF) is defined as

- The ACF measures the linear predictability of the series at time

- If we could do that perfectly, then

In the case of two series this becomes

Stationary time series (TS 1.4) #

Strict stationarity #

A strictly stationary times series is one for which the probabilistic behaviour of every collection of values

- identical marginals of dimensions

- constant mean:

- for

We need something less constraining, that still allows us to infer

properties from a single series.

Weak stationarity #

A weakly stationary time series,

- the mean value function,

- the autocovariance function,

Note:

- We dropped full distributional requirements. This imposes conditions on the first two moments of the series only.

- Since those completely define a normal distribution, a (weak) stationary Gaussian time series is also strictly stationary.

- We will use the term stationary to mean weakly stationary; if a process is stationary in the strict sense, we will use the term strictly stationary.

Stationarity means we can estimate those two quantities by averaging of a single series. This is what we needed.

Properties of stationary series #

-

Because of condition 1,

-

Because of condition 2,

-

- Furthermore,

- The autocorrelation function (ACF) of a stationary time series becomes

Examples of (non)-stationarity #

White noise: We have

Moving average: For the 3-point MA we have

Random walk: For the random walk model

Furthermore, remember

Trend stationarity #

- If only the second condition (on the ACF) is satisfied, but not the first condition (on the mean value function), we have trend stationarity

- This means that the model has a stationary behaviour around its trend.

- Example: if

Joint stationarity #

Two time series, say,

Note that because

Example of joint stationarity #

Consider

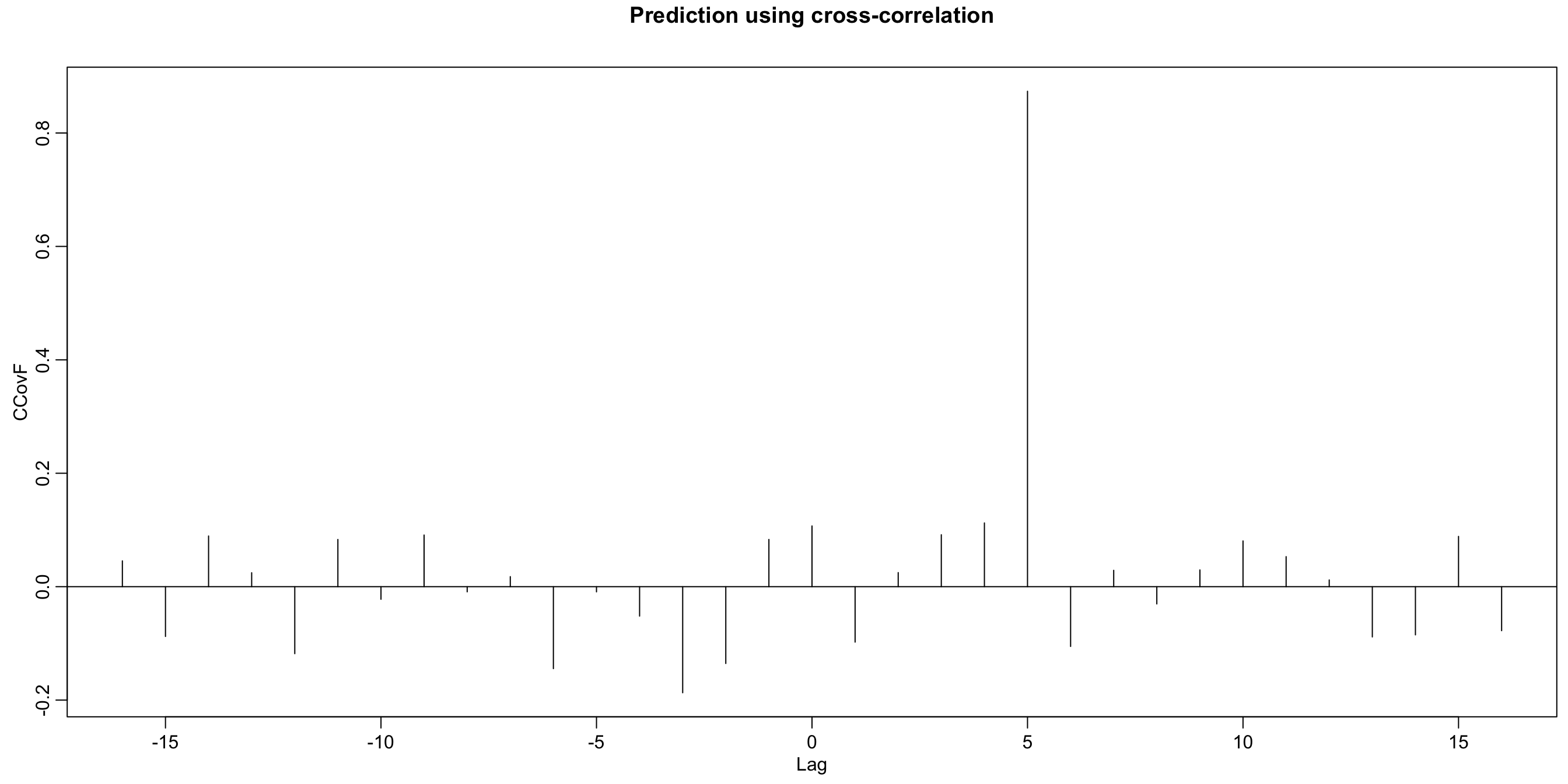

Prediction using cross-correlation #

Prediction using cross-correlation: A lagging relation between two series

If the relation above holds true, then the lag

- If

- We know

- Here

Note this example was simulated and uses the R functions lag and ccf:

x <- rnorm(100)

y <- stats::lag(x, -5) + rnorm(100)

ccf(y, x, ylab = "CCovF", type = "covariance")

Linear process #

A linear process,

Example:

- Moving average The 3-point moving average has

Properties of linear processes #

- The autocovariance function of a linear process is given by

- It has finite variance if

- In its most general form

For forecasting, a model dependent on the future is useless. We will focus on processes that do not depend on the future. Such processes are called causal, that is,

Estimation of correlation (TS 1.5) #

Background #

- One can very rarely hypothetise (specify) time series. In practice, most analyses are performed using sample data.

- Furthermore, one often has only one realisation of the time series.

- This means that we don’t have

- This is why the assumption of stationarity is essential: in this case, the assumed `homogeneity’ of the data means we can estimate those functions on one realisation only.

- This also means that one needs to manipulate / de-trend series such that they are arguably stationary before we can fit parameters to them and use them for projections.

Sample mean #

If a time series is stationary the mean function

Sample autocovariance function #

The sample autocovariance function is defined as

- The estimator is biased.

- The sum runs over a restricted range ($n-h$) because

- One could wonder why the factor of the sum is not

Sample autocorrelation function #

The sample autocorrelation function (SACF) is

Under some conditions (see book for details), if

Testing for significance of autocorrelation #

The asymptotic result for the variance of the SACF means we can test whether lagged observations are uncorrelated (which is a requirement for white noise):

- test for significance of the

- One should expect approximately 1 out of 20 to lie outside the interval if the sequence is a white noise. Many more than that would invalidate the whiteness assumption.

- This allows for a recursive approach for manipulating / de-trending series until they are white noise, called whitening.

- The R function

acfautomatically displays those bounds with dashed blue lines.

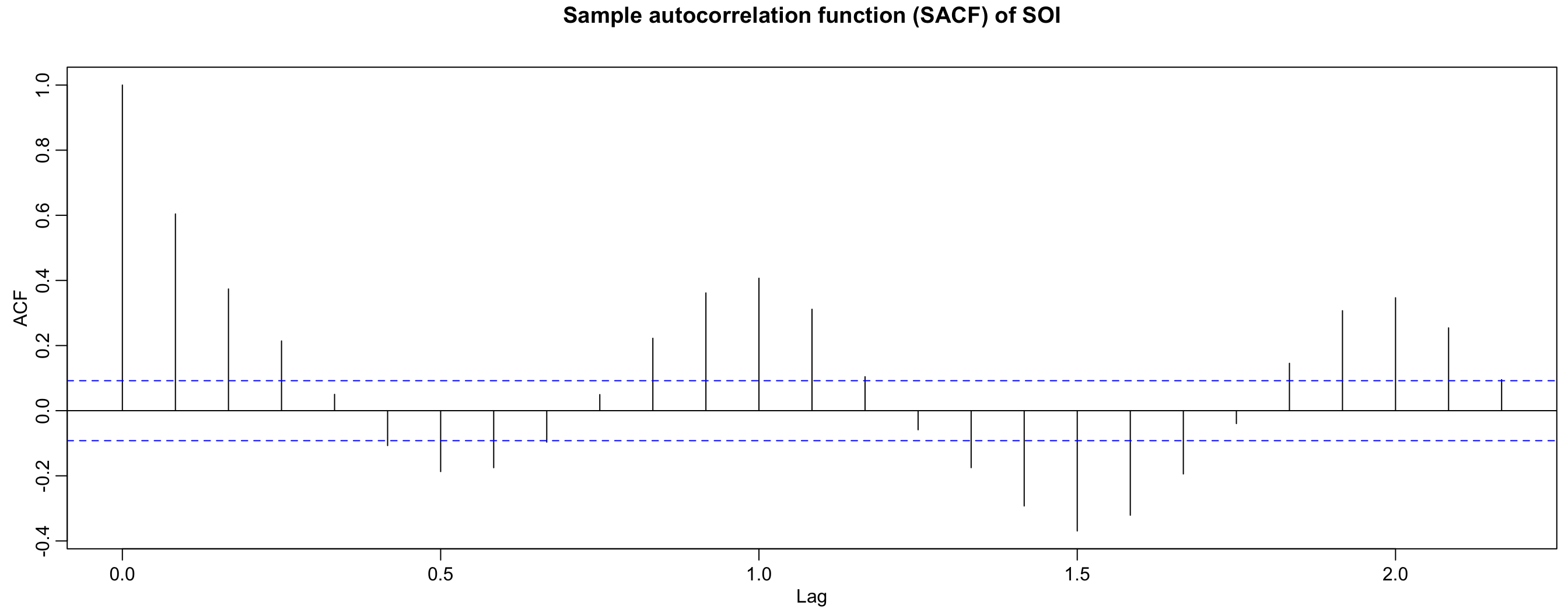

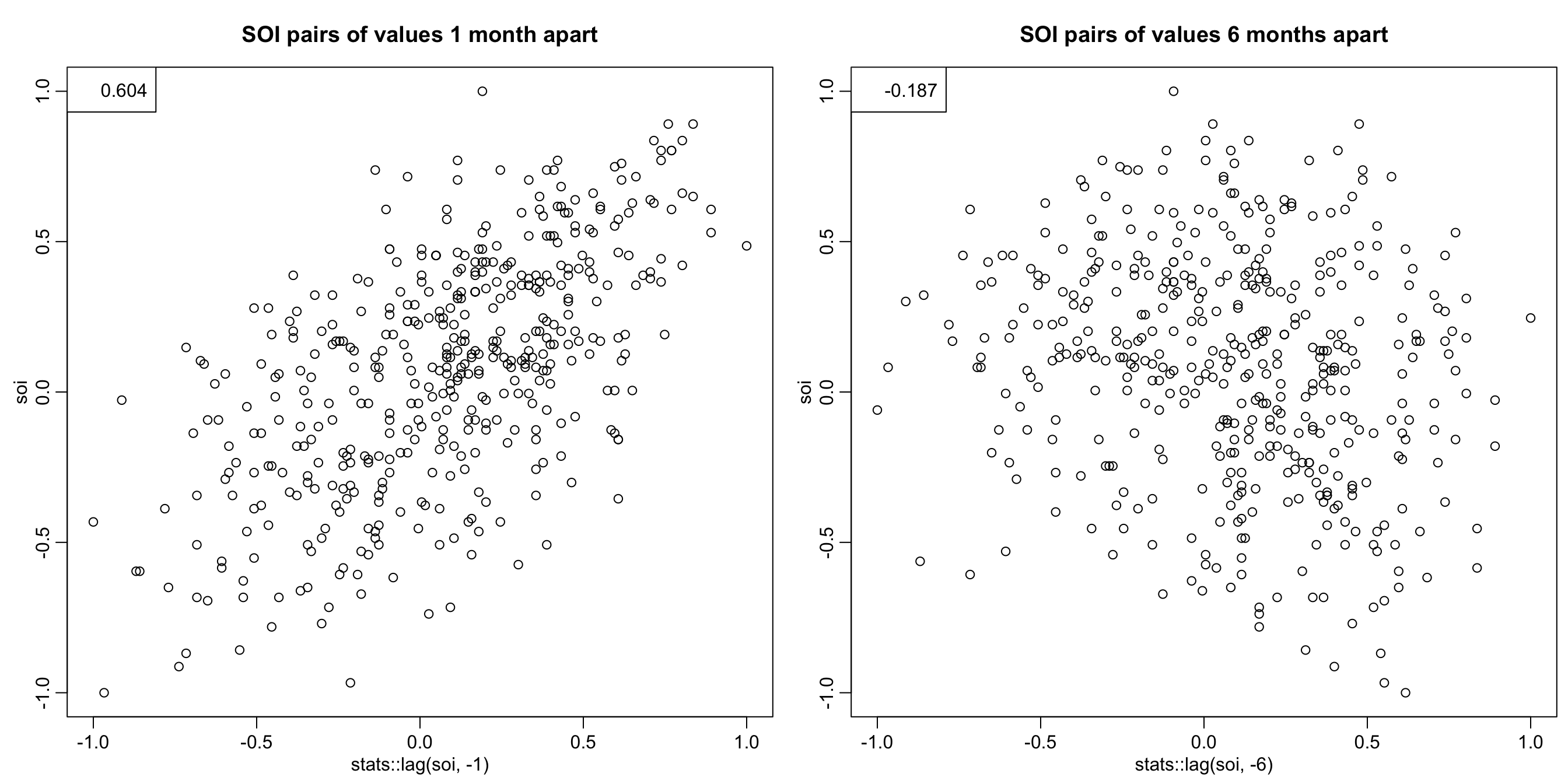

SOI autocorrelation #

acf(soi, main = "Sample autocorrelation function (SACF) of SOI")

r <- round(acf(soi, 6, plot = FALSE)$acf[-1], 3) # first 6 sample acf values

## [1] 0.604 0.374 0.214 0.050 -0.107 -0.187

The SOI series is clearly not a white noise.

plot(stats::lag(soi, -1), soi, main = "SOI pairs of values 1 month apart")

legend("topleft", legend = r[1])

plot(stats::lag(soi, -6), soi, main = "SOI pairs of values 6 months apart")

legend("topleft", legend = r[6])

Scatterplots allow to have a visual representation of the dependence

(which may not necessarily be linear).

Sample cross-covariances and cross-correlations #

The sample cross-covariance function is

The sample cross-correlation function is

- Graphical examinations of

Testing for independent cross-whiteness #

If

This is very useful, and adds to the toolbox:

- This provides feedback about the quality of our explanation of the relationship between both time series: if we have explained the trends and relationships between both processes, then their residuals should be independent white noise.

- After each improvement of our model, significance of the

the boundaries) then we still have things to explain (to add).

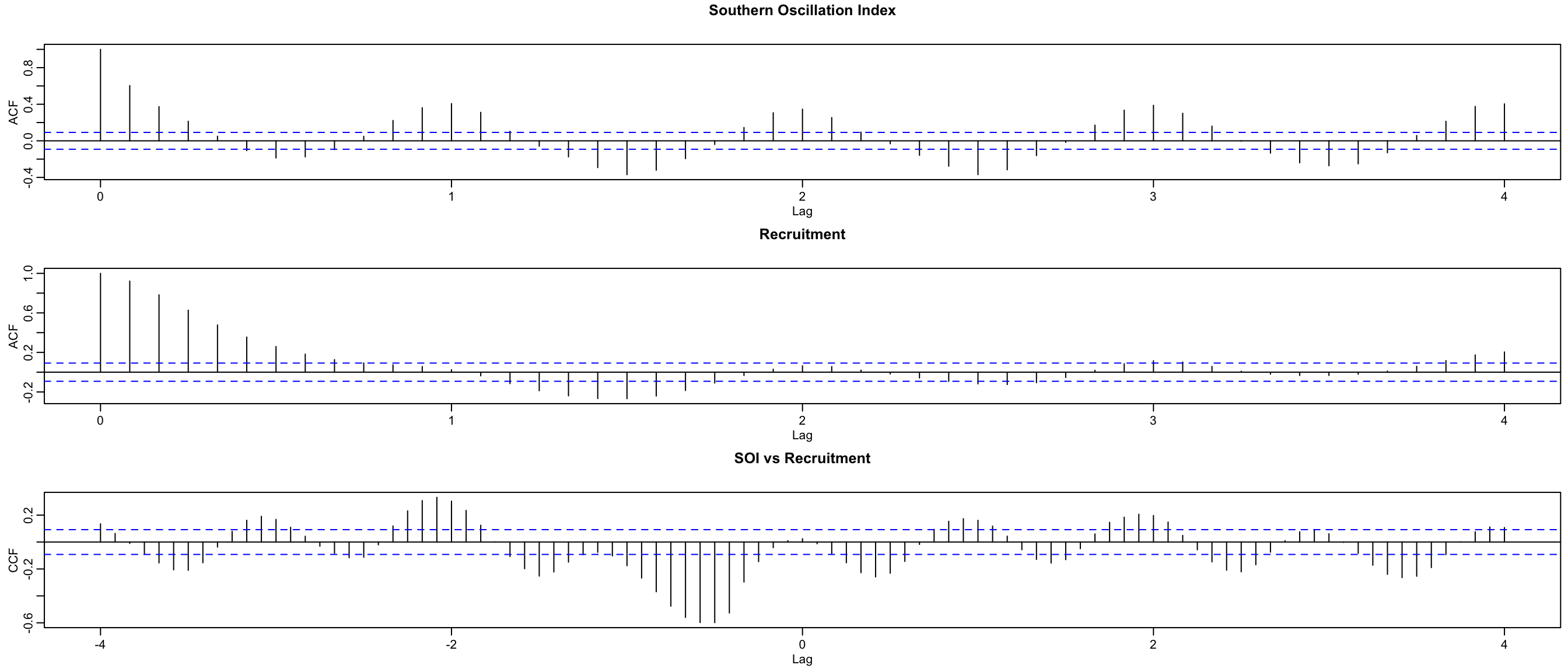

SOI and recruitment correlation analysis #

acf(soi, 48, main = "Southern Oscillation Index")

acf(rec, 48, main = "Recruitment")

ccf(soi, rec, 48, main = "SOI vs Recruitment", ylab = "CCF")

The SCCF (bottom) has a different cycle, and peak at

suggests SOI leads Recruitment by 6 months (negatively).

Idea of prewhitening #

- to use the test of cross-whiteness one needs to “prewhiten” at least one of the series

- for the SOI vs recruitment example, there is strong seasonality which, upon removal, may whiten the series

- we look at an example here that looks like the SOI vs recruitment example, and show how this seasonality could be removed with the help of

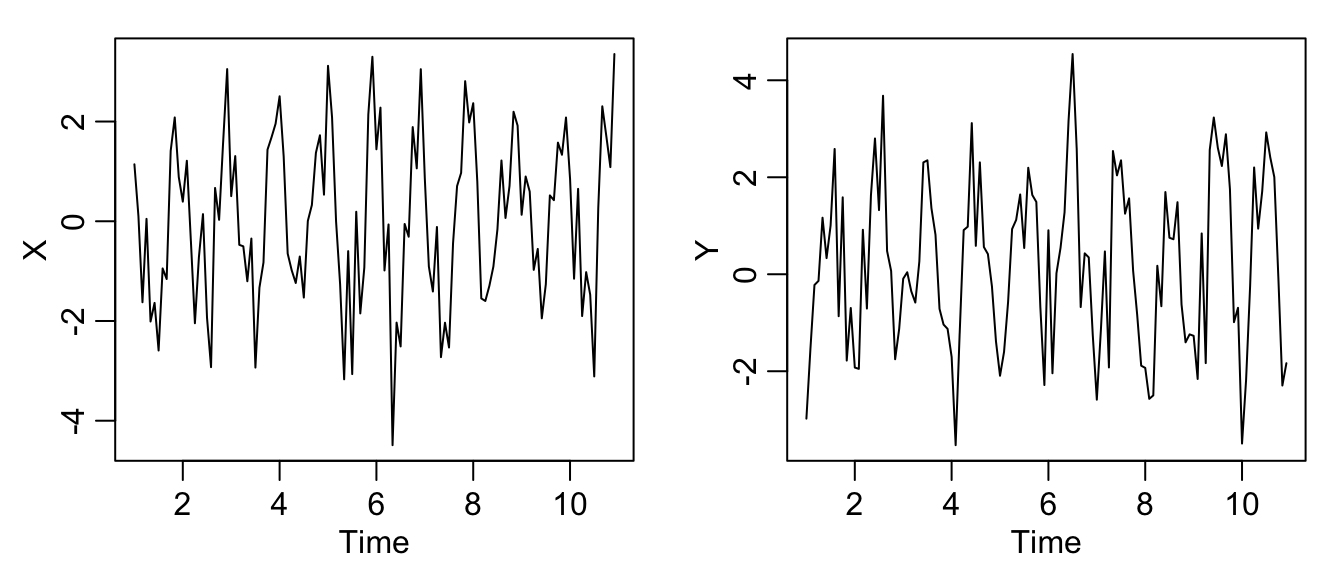

Example:

- Let us generate two series

normals.

- this generates the data and plots it:

set.seed(1492)

num <- 120

t <- 1:num

X <- ts(2 * cos(2 * pi * t/12) + rnorm(num), freq = 12)

Y <- ts(2 * cos(2 * pi * (t + 5)/12) + rnorm(num), freq = 12)

par(mfrow = c(1, 2), mgp = c(1.6, 0.6, 0), mar = c(3, 3, 1, 1))

plot(X)

plot(Y)

- looking at the ACFs one can see seasonality

par(mfrow = c(3, 2), mgp = c(1.6, 0.6, 0), mar = c(3, 3, 1, 1))

acf(X, 48, ylab = "ACF(X)")

acf(Y, 48, ylab = "ACF(Y)")

ccf(X, Y, 24, ylab = "CCF(X,Y)")

- furthermore the CCF suggests cross-correlation

even though the series are independent

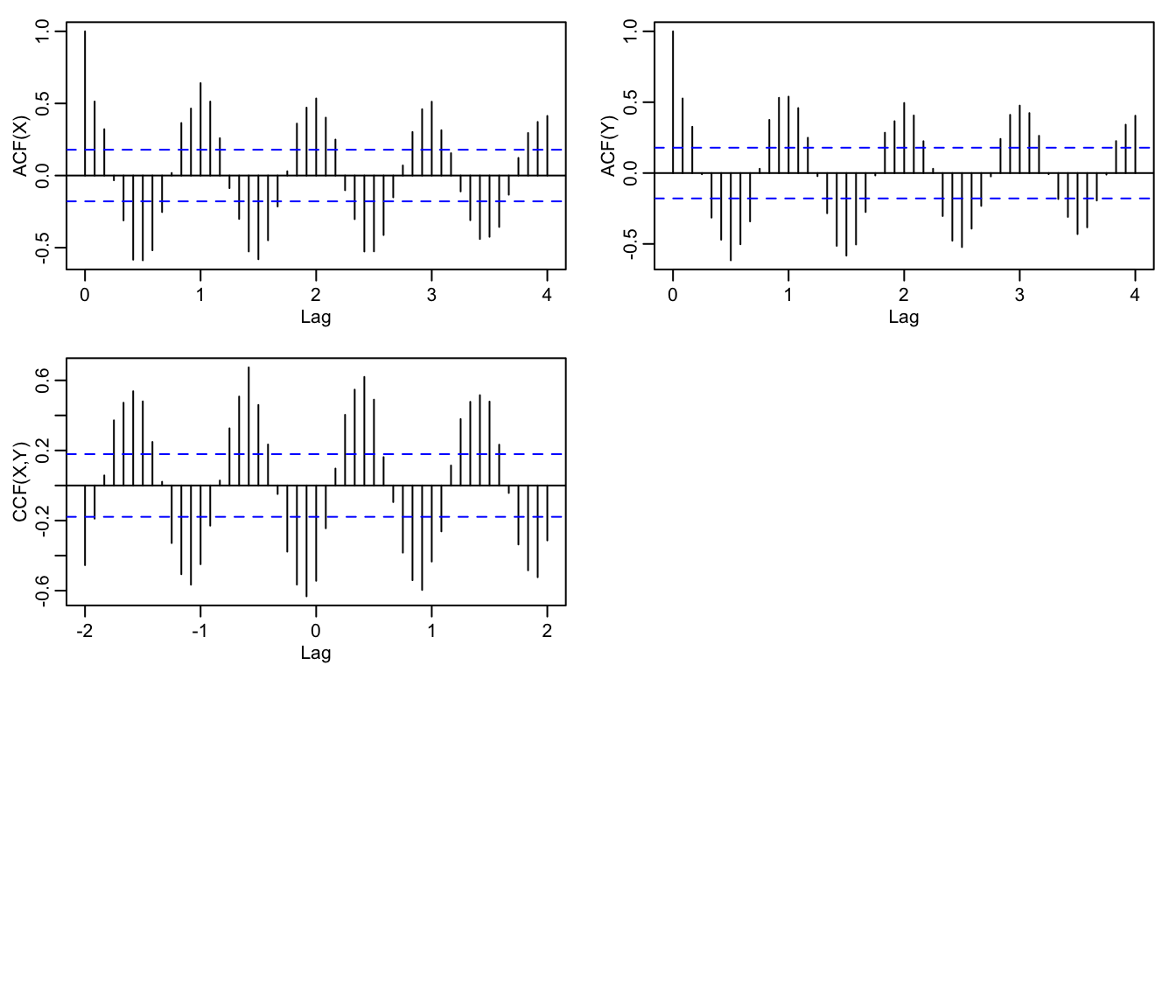

- what we do now is to “prewhiten”

- in the R code below,

Ywis

par(mgp = c(1.6, 0.6, 0), mar = c(3, 3, 1, 1))

Yw <- resid(lm(Y ~ cos(2 * pi * t/12) + sin(2 * pi * t/12), na.action = NULL))

ccf(X, Yw, 24, ylab = "CCF(X,Yw)", ylim = c(-0.3, 0.3))

- the updated CCF now suggests cross-independence, as it should

References #

Shumway, Robert H., and David S. Stoffer. 2017. Time Series Analysis and Its Applications: With r Examples. Springer.